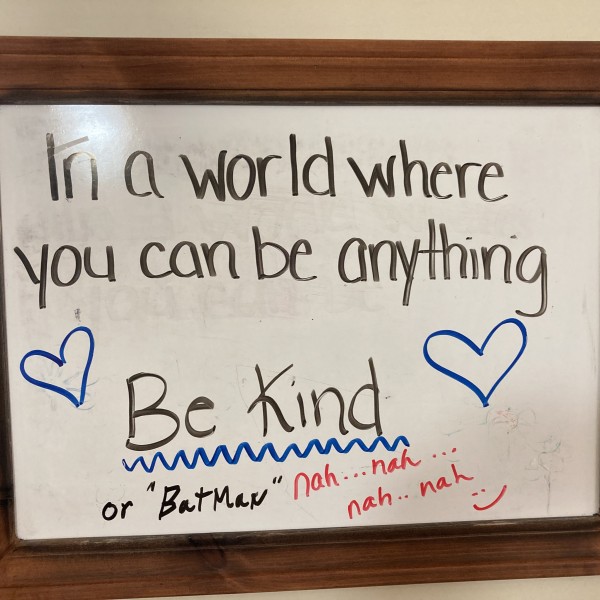

Over my holidays in June, I was visiting a relative who is living in a long-term care home. It is beautiful, warm, and friendly and I am very grateful that there are quality care options within our public health care system. As you exit the elevator on the second floor, there is this whiteboard sign:

Readers who are younger or who grew up without American TV classics may not recognize the significance of the “nah…nah…” syllables. But Canadian kids in the 1960s and early 1970s had very limited TV options—two channels in the pre-cable years—and we watched the kids’ shows that were available over and over, including Batman, a campy comic book-style show which featured the words “Bam!” and “Pow!” while Batman and Robin contained the Joker, the Riddler and the Penguin.

The Batman theme song was equally campy. Its only real lyrics were “Batman! Batman! Batman!” interspersed with surfer guitar riffs that everyone sang as “Nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, Batman!”

The Batman theme song was covered by a range of musicians including The Who, The Kinks, REM and my personal favourite, mod-punk band The Jam. Click here to check out twenty Batman theme covers:

So, if I see something that says “Batman” and starts the pattern of “nah, nah, nah” etc., I smile and I go all in on whatever it is. Nostalgia works that way—and now I am waiting for a resurgence of Rocket Robin Hood where Maid Marian fought along with the Merry Men!

But beyond allowing me a few minutes of nostalgia, this little sign had me thinking about how we set our goals and how we decide who we are going to be in different situations instead of our “go to” which is more about our career goals over who we are as members of the human race.

Even as children, most of us tend to tend to focus on career goals. Children express their future goals with certainty, saying “I am going to be hockey player” or “I am going to be a movie star” or “I am going to be an astronaut.” They don’t allow doubt to creep into the process. They state their plans with purity and conviction. One of my sons had a wonderful ambition, noted in his kindergarten yearbook. When he grew up, he was going to play in the NHL and design Beanie Babies in the off-season.

Growing up female in the 1970s, I met many people who believed that women should remain in traditionally female roles. My sister, who has more of a math-music brain than me, wanted to take Physics in grade 10, but the school guidance counsellor told her that girls should take biology and chemistry if they wanted to do sciences but not physics! It’s a good thing I had no interest in physics, or I would have been determined to prove that girls could, in fact, do and succeed in physics (which would have created a little issue since physics was not really what my languages and humanities brain did.)

But I was determined that I could have whatever kind of career I wanted, even if it was in a more traditionally masculine field. When I entered law school in 1983, more than one-third of my class were women, and the ratio rose to one-half within a few years. Over the ensuing years, we have seen diversity improve, first in law school and then in law practice. Today’s children are much more likely to see someone who looks like them practicing law.

As we got older, we focused on the academic path to our career ambition—law school and a career in law. We knew that there were obstacles. We had to keep our GPAs as high as possible and we had to score well on the LSAT. We began to say things like “if I can get into law school….” Instead of “when I get into law school.”

We continued to refine who we were going to be when we started law school. We focused on studying and finding articling positions so that we could get into the practice area that we thought we like (and then we adapted and revised as many times as was necessary.) When we are law students, we want to be articling students and when we are articling students, we want to be associates. Associates aim to be partners, and partners aim to be department heads or managing partners or perhaps judges. We spend a lot of our time striving. We want to be lawyers who are respected, and we want to be lawyers who clients want to hire. We also want to be lawyers who are compensated fairly in accordance with our organization’s compensation practices—the work is hard and draining, so we may as well be well-paid—but this is a divisive issue in a profession where we all think we should be at the upper end of the compensation scale.

If practicing lawyers were asked the question “In a world where you can be anything, what would you be?” many of us would answer based on our current career aspirations. How many of us would have responded with the word “kind”?

As lawyers, we rarely encounter encouragement to cultivate kindness. In our profession, kindness can be interpreted as weakness, and we learn very early on to adopt a neutral if not adversarial demeanor.

At a lawyer well-being event I attended this spring, one participant opined that one of the root causes of poor lawyer mental health was that many of us became lawyers to help people, but our work—particularly in the context of litigation—can actually harm people. And I think this lawyer is correct.

I didn’t enjoy litigation, but I remember doing my first cross-examinations. I tried to be courteous and respectful, but the zero-sum game litigation realm means that you sometimes must make people feel uncomfortable and crush their hopes and dreams (of getting rich off your client, say.) I found it much easier to be humane in corporate-commercial transactions.

When I moved into human resources law, I approved terminations of employees and designed downsizing plans, among other activities. These are not generally opportunities to show kindness to our fellow travellers, but I took comfort that we gave employees appropriate opportunities to improve their performance and that we treated employees fairly (even if not generously.)

In a world where you can be anything, you can be humane and fair….. It just doesn’t have the same ring for those of us who want to have a positive impact on our communities.

We can build kindness into our volunteer work, and we can do our best to treat our co-workers with kindness. Step one is to recognize whether you have a need for more positive interactions with people, and step two is learning to turn off our lawyer brains so that we can listen without judgment or by offering solutions. I frequently fall short of my intentions to treat everyone with kindness, but that doesn’t mean I can’t forgive myself and start trying again.

One of the most impactful acts of kindness I experienced was from a lawyer I didn’t know. I was several months pregnant and was waiting for my (then) husband to pick me up to take me to an ultrasound appointment. I don’t know if ultrasound procedures have changed, but in those days, you had to drink four eight-ounce glasses of water an hour before the procedure—your full bladder somehow gave the sonogram technician better visuals. So, I stood, waiting, in the lobby, of my building, very pregnant and with a bladder ready to burst because he was, as always, running late.

Three lawyers who worked at another firm in my building came through the lobby on a coffee run. I knew who they were, but I doubted that they knew who I was. I continued to stand, waiting, and was still there when the three lawyers returned with their coffees. One of them approached me and said “I hope that the person you are waiting for comes soon. You look like too nice a person to be kept waiting.”

My anger and frustration melted away—someone cared that I was waiting and took the trouble to say something kind to me. He happened to be another lawyer, but I realized the power of being kind to a stranger and that being a lawyer didn’t mean you were above practicing small acts of kindness. Ironically, the kind lawyer moved three houses down from me a year or two later. I wish I had thought to ask him if he remembered me as the pregnant woman waiting for a ride and if he knew I was a lawyer—but I think there was a good chance that he went around saying kind things to people when he could and that this incident may not have stood out for him.

In a world where you can be anything—including a lawyer-- what do you want to be? Do you want to be a lawyer who puts blinders on to human suffering around them, or do you want to be a lawyer who sees opportunities—however small-- to respond with kindness?

We don’t have to narrowly define ourselves as lawyers—we can be the people we want to be, helping those in need and working together to make our profession and our communities a better place.

And, at least once per year, we can be Batman, or Wonder Woman, or Black Panther, or Thor. Maybe this is why Halloween has survived in our culture while many old English observation days have fallen by the wayside.

Oh--and I am not saying I’m Batman. But have you ever seen me in the same room as Batman?

In a World Where You Can Be Anything