We are Stronger Where We are Mended

It is trite to talk about how we all spent more time in our homes during the pandemic. We have all heard about people’s motivation to renovate their houses or to buy new furniture after spending day after day immersed in the imperfections of our houses, causing a run on building supplies.

I had a different experience. While my house has many yet-to-be-rectified imperfections, I noticed items in my house that I took for granted and found enjoyment, even beauty, in items that formed backgrounds. I often worked from my dining room during the work-from-home era, and when I needed to get up and move around, I gravitated to my adjacent living room. And in my living room, I have a glass cabinet where I keep special, and often fragile, keepsakes.

One of my most special things in that cabinet is a Japanese porcelain doll that my father brought home from a tour around the world in 1969. I still don’t understand exactly what he was doing, but my dad was a pilot and it involved flying a Hercules to different countries for promotional purposes. I think I was seven, and what I remember is that he was gone over Christmas which was sad. But when he got home, he had brought dolls for my sister and me from many of the countries he had visited.

Dolls needed names so we would ask our parents what kind of names girls had in the different countries. The only name I can remember, fifty plus years later, is the name of the Japanese doll. Her name is Yoko. Looking back, it makes me laugh. No doubt I asked my parents for Japanese girls’ names, and they gave me a name that they knew from the news—Yoko, as in Yoko Ono, as this was around the time of the famous John Lennon and Yoko One Bed-in in Toronto. My parents thought that rock music was an abomination, but even they knew who The Beatles were!

Yoko, the doll, was not the type of doll a little girl could play with. She is made of porcelain, dressed in red silk kimono with a gold obi, and has ornately styled hair under a circular flat hat. She is also mounted on a black lacquer music box, which still plays. Looking at Yoko more closely, since I had oodles of time at home, I noticed that she needs a few small repairs to her hair and hat. I made a note to self (yet to be acted on) to find someone someday who repairs Japanese dolls.

A lot has happened to me over those fifty years. My dad’s international adventure was a harbinger of change coming to my family—my parents separated not long afterwards, and I had the experience of being the first student in my elementary school from a divorced family. I vividly remember my dad telling me not to talk about our family turmoil, and I didn’t. I didn’t ever discuss what was happening with my best friend, and it wasn’t until I was in high school that I met friends whose parents were divorced with whom I could discuss my feelings.

I know now that I was being urged not to air the family dirty laundry broadly, but my young brain interpreted this as shame, and I felt lesser-than all the kids from two parent homes. This was the early 1970s, when the Divorce Act modernization was new, and I can now recognize that my parents were doing their best navigating unchartered territory. At one time, when I was around ten, they thought I would benefit from talking with a psychologist and I reluctantly went. But all I could remember while being in her office was that I was not supposed to talk about our family troubles. I think I resolved to instead be perfect so that no one could question me or ask me to share private information.

For most of my life, I wanted my father to understand what I had experienced and own the many ways that I felt hurt. We tried a few times, but I didn’t ever succeed in finding words that he understood about my pain. But when he received a terrible diagnosis last winter—Lewy Body Dementia—my need to make him understand me faded. I no longer wanted to live in the past. I wanted to concentrate on the time we had left.

Recently, I learned about Kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing broken ceramics with gold, which emerged in the 1400s. Before that time, broken items like tea bowls were repaired with hardy and handy metals which left a functional, but ugly, bowl with scars. In the 1400s, however, artisans began repairing ceramics with gold, with the intention of bringing attention to, rather than hiding, the breaks. The lines of gold on the repaired item were beautiful, and the breaks became artistic components rather than scars.

Not only were the gold bonds beautiful, but they were also strong. The tea bowls, and other items, were stronger where they had been fused with gold.

Kintsugi has become a metaphor for healing. Lines of gold that weld breaks can be signs of strength and beauty. One author writes:

When something breaks, it is changed forever. Shape, structure, form, and function may all be affected, and the way it is put back together, the bonds forged to fix it, become as much a part of its new incarnation, as its older parts…. In an age where we are all too focused on perfection and strength, kintsugi teaches us that imperfection and fragility are two things to be celebrated.

In law, we pretty much do the opposite of celebrating imperfection and fragility. Lawyers, me included, are plagued by perfectionism, and while adaptive perfectionism can motivate us to produce excellent work products, perfectionism can be maladaptive when we criticize ourselves harshly for errors, no matter how minor. We often want to castigate ourselves before someone else has the chance to!

And I learned early on in my law career that fragility was not a desirable trait for lawyers, so I hid mine. I learned to make dark jokes about uncomfortable subjects and to never let my emotional reactions, or weaknesses, show.

I had cracks before I went to law school and entered the legal profession, and since that time I, along with most lawyers I know, have suffered many more. And like the early Japanese craftsmen, we repaired our cracks with whatever was available and did our best to hide both our cracks and our repairs. Many of our fixes were not durable—like alcohol use. Lawyers felt better for awhile before shattering into even more pieces.

I tried to heal the cracks I experienced from family breakdown by attempting to be perfect, thinking that if I could become perfect, my cracks would heal. This was superficial, like applying cosmetics to cover wrinkles or blemishes. It worked for awhile if you didn’t look too closely. While the pain associated with some of those cracks has faded with time, they are still present and formed part of who I am, and I had to learn to accept them.

The Lawyers Helping Lawyers movement of the 1980s brought the equivalent of kintsugi to lawyers, healing through professional counselling, peer support and medical treatment when needed. This led to the formal incorporation of Assist in 1996, an organization effectively devoted to kintsugi. Since then, many of us have been repaired with gold—professional counselling, medical treatment, peer support—and our repairs are beautiful, they make us beautiful, and we are stronger where this gold holds us together than we were before.

The fact that we can repair our cracks with gold and become stronger is important given the findings of The National Study on the Psychological Health Determinants of Legal Professionals in Canada. More than half of the 7300 survey respondents reported experiencing psychological distress and burnout (not including those who were experiencing anxiety and depression.)

More than 20% of the National Study (p. 28) respondents reported very high levels of psychological distress, with another 37% reporting high levels— more than half of lawyer participants are stressed a high or very high level. Women, young lawyers (under 35), disabled lawyers and lawyers identifying as LGBTQ2S+ community had the highest rates of psychological distress. There is work to be done in our profession to both heal and strengthen our colleagues.

Psychological distress can be the canary in the coalmine as symptoms of psychological distress are similar to symptoms of more serious mental health conditions and can, if untreated, lead to clinical conditions. We need to pay attention to them and seek help before they worsen.

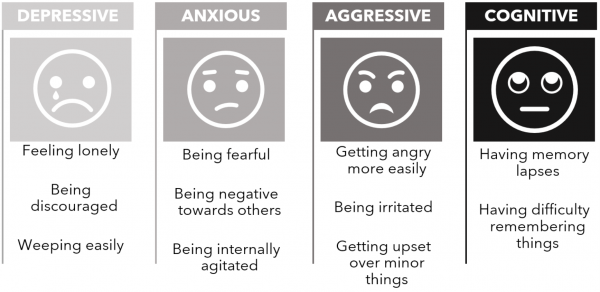

I love the graphic the National Study uses to illustrate symptoms of psychological distress (page 29):

I am tempted to print it out—or bring it up on a screen—weekly or even daily and self-evaluate. A bad day or a bad week must be viewed in its context, but if you see continuing patterns, you may want to seek support. Experiencing these signs does not mean that you are on your way to full-blown mental health conditions, but you do not need to wait until you have a diagnosable condition to seek help. Assist’s professional counsellors tell us that the earlier you engage with helping resources, the more easily issues are resolved.

If I can pursue the kintsugi metaphor, I see these psychological disturbances as hairline cracks in our porcelain. The cracks may remain on the surface, never changing, but it is also possible that they will increase in length, width, and depth, causing deep ruptures requiring extensive repairs.

I am learning to see the beauty in a spider’s web of gold repairs that makes each of us unique and strong. I take great comfort in the fact that we are stronger where we have been mended.

In our profession, hiring committees have tended to look for articling students and young lawyers whose porcelain does not betray any cracks. But If I were a managing partner or a lawyer manager, I would not weed out the ones who may have experienced challenges. I would look for mends and cracks, knowing that lawyers and students who have sought and implemented help for mental health and substance use issues will be more aware of signs that they are experiencing stress and they know what works for them in terms of recovery. This is one of the strengths that arises from the repair process.

According to the National Study, almost half of articling students have experienced a mental health diagnosis since beginning their practices. This is the reality we are facing. We can either embrace our young colleagues who are more open about their inner workings, or we can be left behind. I am choosing to embrace kintsugi, applying the metaphor to myself. All the traumas, large and small, that I have experienced can be reflected and celebrated rather than hidden, and I am stronger because of them.

And applying the kintsugi metaphor to Assist, our professional counsellors and peer support volunteers are the artisans who source and administer the gold that is healing in your cracks, making you stronger and giving you unique beauty.

Are you feeling cracked and broken? You are not alone. Our profession is filled with people who have experienced deep challenges, weathering all manner of storms. We have cracked, we have broken, we have mended, and we have gotten back up to face the world another day. If you feel fragile or are concerned about your cracks and whether your mends will hold, call us. We can help.

Loraine

PS: if anyone has a contact who repairs Japanese dolls, please let me know!